Archbishops Eamon Martin and John McDowell Speak from Normandy

“Today we commend our D-Day chaplains. As war threatens the world, we stand for peace and reconciliation”

Speaking in Normandy at the prayer service to mark the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landing, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh, Archbishop John McDowell, and the Archbishop of Armagh, Archbishop Eamon Martin, have reflected together on the sacrifice of those who gave their lives on D-Day 1944. The Archbishops delivered their respective addresses at the Royal Irish Regiment Service of Remembrance at Ranville Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery, near Sword beach in Normandy, this afternoon.

Archbishop McDowell paid tribute to the Revd James McMurray-Taylor, a Church of Ireland chaplain who landed on Sword beach, on 6 June 1944, and recalled his own experience of growing up in East Belfast among, and alongside, veterans of the Second World War.

Archbishop Martin spoke of the Christian witness of Father John Patrick O’Brien SSC, born in Donamon, Co Roscommon, and ordained in 1942 as a priest for the Mission Society of Saint Columban. However, due to wartime travel restrictions for missionaries, he trained as an army chaplain and accompanied the D-Day invasion in Normandy. Archbishop Martin said, “Father Jack O’Brien and the other chaplains ministered to soldiers of all denominations from every county on the island of Ireland … It has been largely forgotten – perhaps conveniently at times – that tens of thousands of men and women from all over the island of Ireland served side by side during the Second World War. Unlike many others, they were volunteers, rather than conscripts – personally motivated to serve the cause of peace and freedom and justice.

“As war and violence once more threaten to destabilise our continent and our world, Archbishop John and I stand here together at Ranville, witnessing to peace and reconciliation, to fraternity and common humanity.”

“Fraternity and common humanity: that is what our brave and generous chaplains stood for in 1944 as they cared for the spiritual and emotional needs of so many in life and in death … the chaplains carried no arms – save the power of prayer and the Word of God. Their faith gave them all the strength they needed,” Archbishop Martin said.

Ranville sits a short distance from Pegasus Bridge, and has the distinction of being the first village in France to be liberated on D-Day.

Archbishop Eamon Martin, Archbishop of Armagh, Primate of All Ireland.

Archbishop John McDowell, Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.

Archbishop John McDowell and Archbishop Eamon Martin’s Reflections can be found below:

Archbishop John McDowell

A reflection on the Revd James McMurray-Taylor, Church of Ireland chaplain to the First Battalion of the Royal Ulster Rifles 1943-47, who landed on Sword Beach, Normandy, on D-Day:

Although it is at the side of a main road leading into Enniskillen, the little Arts and Crafts Church of Saint Patrick’s, Castlearchdale, where the Revd James McMurray-Taylor is buried, is a tranquil enough spot. It wasn’t always so, and for the war years in the 1940s there was a large military presence, most distinctively of Catalina and Shorts Sunderland flying boats. Indeed, it was from Castlearchdale that two of the Catalinas which were instrumental in the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck were launched.

It would be tempting to think that it was the rather glamorous presence of so many GIs that inspired James McMurray-Taylor to volunteer as a Chaplain to the Forces in 1943, but in fact he was a curate in the parish of Saint Mary’s on the Crumlin Road in Belfast at that time. As far as I know, there is no written record of why he volunteered but it is clear from all that we do know about him that he was a very dutiful man in an age when a sense of duty counted as a higher virtue than it does today.

Duty to his country and, overwhelmingly, duty to his God and to his vocation as a priest. There was a soldier in another war who, in an attempt to explain to his distraught wife why he had to go to war, reminded her that “I could not love thee half so well, loved I not honour more”. Honour and duty – old fashioned words which are now lost to ordinary speech, but which explain a lot about people like James McMurray-Taylor.

He was certainly someone who did not seek the limelight. All the accounts of how he conducted himself as a chaplain – blessing soldiers from every Christian tradition and none before battle, burying the dead, both British and German, with the respect due to human dignity, toiling in the warm stench of death and hot sun of a battlefield to recover name tags and personal effects also from German and British alike, to be returned to their loved ones – are evidence of deep faith and dedication.

There is one letter from James, I think, in the Regimental Archive. It was written twenty years after he had been demobbed and seems to be in response to someone who was writing up the history of either the Regiment or Chaplaincy, and also inviting him to buy a regimental tie! The letter in response, though short is very revealing. He remembers the parachute training in October-November 1943 and he “thinks” it was in February 1944 that he joined 1 RUR, which as far as he can remember was going to make an air assault on Japan.

Although in every sense a hero, there is nothing of the heroic in his style and manner. He was a man dutifully doing his job. He received no special treatment when he returned to the Church of Ireland in 1947. He was curate in charge of a small parish in County Donegal and then one in County Derry before ending up with two rural and parishes in County Fermanagh, where he stayed until he retired in 1980.

Interestingly he kept up his military connection after his demobilisation and was awarded the Queen’s Jubilee Medal for services to the Army Cadet Force in 1977. He clearly never sought preferment, was never made a canon of a Cathedral despite being editor of the Diocesan Magazine (the most thankless of all tasks) for twelve years.

I grew up in Belfast in a housing estate which included a long terrace for disabled ex-servicemen. All of the residents had been physically damaged – usually with the loss of a limb – although I cannot remember any sense of bitterness. In other words, I was surrounded by men like James McMurray-Taylor. Extraordinary, ordinary people who did their duty and did it cheerfully in often very difficult circumstances.

Pretty well all of my father’s and mother’s generation fought in the war. I had two Merchant Navy uncles who sailed on the convoy ships to Archangel and Murmansk and another uncle who had fought in both the First and Second World wars. One of our neighbours had fought south of the Irrawaddy River in Burma and another had been involved in the doomed attempt on Narvik in Norway.

The Great War had been the end of faith for many. Those who had grown up in an easy peace and a superior culture. Those who were confident in the onward march of civilisation, because they had never had their self-confidence tested; who did not know the wickedness that men were capable of. In the century before that war, the Churches had domesticated God and harnessed him to their purposes. He had become their asset and their patron, rather their Judge and their Redeemer.

That was not so much the way with the Second War, where the moral case for the destruction of Nazi Germany was unambiguous even before the men we are remembering today fought their way across Europe and found the horrors of Belsen and Auschwitz. And perhaps the remarkable energy and clear-sightedness of that generation who fought in the war and then went on to create the welfare state in health and housing was a consequence of that moral clarity, so unlike the dark years of the 1920s and 30s when many of those who had fought in the Great War were left in poverty and misery by a system of class privilege which had not yet been broken.

That, of course, is speculation. However, what is not speculative, but concrete and clear, is a life like that of James McMurray-Taylor. Confident in the rightness of the cause for which those whose souls he had the care of were fighting-confident but not self-righteous. Putting his trust in the God of all the nations, a God of justice and humanity, he did his duty on the battlefields of Europe during the war and his duty after the war, in a quiet corner of the country he loved, serving the God who he loved – and in his eyes there was no incongruity between the Lord of Hosts and the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace.

Archbishop Eamon Martin

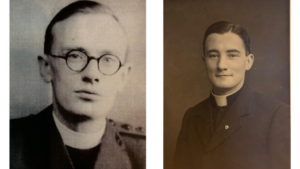

I have brought with me today a photograph of Father John Patrick O’Brien SSC, a treasured possession of his relatives back in Ireland. Father John was born in Donamon, County Roscommon at the end of 1918, just a few weeks after the guns of the so-called ‘Great War’ fell silent. At the age of 17, Jack – as he was known to family and friends – left Saint Nathy’s College in Bellaghadereen with a strong sense that God was calling him to be a missionary priest in the Far East.

He was ordained in 1942 for the Society of Saint Columban, but because of the wartime travel restrictions he was unable to receive a missionary placement. Instead, the young Father Jack decided to train as an army chaplain. He was assigned to the Royal Ulster Rifles, and to accompany the D-Day invasion, landing here with the Allies on Sword Beach, eighty years ago.

I have no doubt that Jack O’Brien would have been inspired as a young person by stories about the saintly Father Willie Doyle, a chaplain in the First World War who was killed by a German shell while running out to rescue two wounded soldiers in No Man’s Land in 1917. Many stories were told of Father Doyle’s bravery and deep faith, and how everybody in his battalion held him in great respect – Catholics and Protestants alike (1).

For the newly ordained Father Jack O’Brien, the battlefields of Normandy and beyond were to become his first parish; his mission: “to give, and not to count the cost”; to serve God by keeping hope and human dignity alive amidst the horror and brutality of war.

As a Catholic chaplain he offered the consolation of prayer and the sacraments to everyone who asked – especially Confession, the Eucharist and the Last Rites – and he never forgot a word of compassion and encouragement for the wounded, the worried and the war weary.

The troops called him ‘the fighting padre’ because Jack had been a boxer in his student days, and several anecdotes are recorded of his positive attitude and good humour. They say he sometimes ‘visited the men in their dugouts for a few hands of poker, often with rum scrounged from the quartermaster,’ and once, when a newly arrived officer fainted and almost fell into an open grave during a burial, Father Jack grabbed him saying, ‘Now, there’s no need to be in a hurry. All in good time.’

As war and violence once more threaten to destabilise our continent and our world, Archbishop John and I stand here together at Ranville, witnessing to peace and reconciliation, to fraternity and common humanity. Speaking last month to a group of Nobel Peace Laureates in Rome, Pope Francis reminded them of the Nobel lecture given by Martin Luther King, Jr, in 1964 when he said: ‘We have learned to fly the air like birds and swim the sea like fish, but we have not learned the simple art of living together as brothers’ (2).

Fraternity and common humanity: that is what our brave and generous chaplains stood for in 1944 as they cared for the spiritual and emotional needs of so many in life and in death. Like all caught up in the nightmare of war, the chaplains experienced the horrors and trauma of the battlefield, but the chaplains carried no arms – save the power of prayer and the Word of God. Their faith gave them all the strength they needed to tend to the wounded, to comfort the dying, to ensure Christian burials for the fallen, to help identify the dead and to break sad news with relatives at home.

Father Jack O’Brien and the other chaplains ministered to soldiers of all denominations from every county on the island of Ireland. The tensions, sectarianism and suspicions of home are of little significance when shells are falling on brothers and sisters in arms who are being struck down, wounded, dying and grieving together.

It has been largely forgotten – perhaps conveniently at times – that tens of thousands of men and women from all over the island of Ireland served side by side during the Second World War. Unlike many others, they were volunteers, rather than conscripts – personally motivated to serve the cause of peace and freedom and justice.

Within six to ten months of D-Day, the RUR Battalion had helped to liberate village after village across northern France, Belgium and Holland, at last reaching Bremen in Germany. At that stage Fr Jack wrote home saying that sadly not many of his original flock were left, but according to his commanding officer: “(Jack’s) perennial cheerfulness was the salvation of many a drooping spirit in the difficult days which confronted us”.

After the German surrender, Father O’Brien’s kindly and cheerful presence continued to be a source of great comfort to the displaced and traumatised people they met along the way. Ever the missionary, he travelled on to Egypt, where the Battalion was helping to guard the Suez Canal, and by 1946 he was with them in Palestine – a long way from the beaches here where he had first landed.

But Father Jack’s superiors in the missionary society of Saint Columban had not forgotten about him. It was time for him to be recalled from his responsibilities as an army chaplain. In 1948 he was assigned as a missionary priest in Mokpo, on the southern coast of South Korea.

When I think of his life, I am reminded of that passage in Saint Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians when he wrote, ‘I do not fight like a boxer beating the air. No, unlike runners and athletes who train to compete in the games for a perishable wreath, we do it to get a crown that will last forever (1 Cor 9:25-27).

Father Jack O’Brien’s story of courage and self-denial continued well beyond D-Day. In 1950, when the communist forces began to invade South Korea and were approaching his parish, he refused an offer from American troops to be evacuated to safety, preferring instead to remain with his people and serve them to the end. He was captured and imprisoned, and after a long march at gunpoint towards North Korea, he was executed in the massacre at Taejon, a month before his 32nd birthday. His body was never found or identified – he was martyred for his faith and belief that ‘neither death nor life can ever separate us from the love of God.’

Coincidentally the soldiers of the Royal Ulster Rifles 1st Division were also called to Korea in 1950, suffering many losses in the Battle of Happy Valley. In 2013 a memorial stone was erected in Seoul to record and honour their contribution. Fittingly it includes the name of their former chaplain, one Father John Patrick (Jack) O’Brien who had served and prayed with them on these roads and fields of Normandy, 80 years ago today (3).

(1) See To Raise the Fallen, Father Willie Doyle, ed Patrick Kenny, Veritas (2017)

(2) Pope Francis to participants in World Meeting on Human Fraternity event, 11 May 2024

(3) I am grateful to Father Neil Collins SSC and to Mairead O’Brien for sharing with me the fruits of their research into the life of Father Jack O’Brien.

You must be logged in to post a comment.