Every year the diocese of Derry issues a directory listing all the priests of the diocese. It was with a sense of loss that I discovered in the January 2014 edition that, having moved to Armagh, I was no longer counted among the priests of Derry. It wasn’t that I hadn’t settled in Armagh, or even that I was pining for the town I loved so well! It was one of those moments when I realised that I was ‘in between’ – I’d moved on from the city of the oak grove to new pastures; I now had a new flock, new responsibilities and challenges in the orchard county and beyond.

The life of a priest is bound up with his diocese. At ordination we join a ‘presbyterate’, a brotherhood or fraternity of priests within a particular local church or diocese, as co-workers with our bishop. We become members of a family whose ties are not from flesh and blood, but from the grace of Holy Orders which binds us together in spiritual and pastoral belonging to the people of the parishes in our diocese. That sense of belonging, consecrated by the laying on of hands at ordination, is still strong in me. This connection was somehow disrupted when I made my way from the pastures of Columba and Eugene to the territory of Patrick, Malachy, Brigid and Oliver Plunkett.

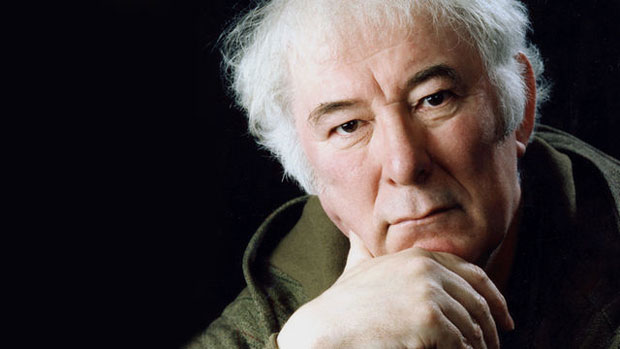

Among my earliest memories as a pupil of St Columb’s College in Derry is of hearing the sound of the College bell in Bishop Street. Our English teacher reminded us that was the same bell which Seamus Heaney had written of ‘knelling classes to a close’ in his powerful poem, ‘Mid Term Break’. We studied the poem in my first year and I remember thinking Heaney was just around my age when he made that sad journey home for his younger brother’s funeral – only he was a ‘boarder’ who had to leave his beloved Bellaghy home as a young boy to find himself bereft and far from home in the City. He has written about the unforgettable homesickness and grief he felt during his earliest schooldays at St Columb’s.

Heaney’s rootedness and attachment to his home place and family in Mossbawn was to stay with him all his life. So much of his poetry and thought sprung from his sense of belonging to place and people in the Bellaghy area. It was deep down in him, the place in which he grew to know who he was – not just as a child, but also as an adult. Here was his personal Mount Helicon – the source of his understanding of himself, the font of his poetic inspiration. His early poem ‘Personal Helicon’ draws this out in a striking way. It is also an example of the way in which Heaney’s poetry was steeped in the Classics he first learnt at St Columb’s. As pupils we struggled with Ovid but young Heaney seems to have lapped up his Homer and Livy and Virgil.

Life is full of curious intersections of events and places and people. In the chapel in Bishop Street I remember one of our teachers telling us that the famous Seamus Heaney would have sat on those same pews as a young ‘first year’ like us. I have since contemplated him sitting there, perhaps praying for his family and people at home, especially his grandfather, father and mother. Perhaps this was the place that a homesick young County Derry boy noted in his mind’s eye the memories that would later brim over in his poetry – like peeling spuds with his mother; seeing her out hang out the sheets to dry; the sounds of his father digging, the smells and sights of the turf banks, cattle and fields around home. Was it there that ideas were set down in chrysalis that would later burst out in the lines of his poetry? Links and connections are made in early life which last a lifetime. In that same chapel, as a young member of the Gregorian ‘schola’, I chanted for the first time the words from the Christmas antiphon: ‘Cantate Domino Canticum Novum’ – ‘Sing a New Song to the Lord’, words I would later choose for my Episcopal motto.

Moving to a new diocese with new priests and parishes has given me a greater sense of belonging to the wider, universal family of the ‘one, holy catholic and apostolic Church’. I have come to realise that ‘parish’ ought never to be ‘parochial’ in the pejorative sense of the word. It is merely a gateway, threshold or opening to something beyond itself – the diocese, the universal Church, and on to the eternal kingdom of God. Last year at the Synod of Bishops in Rome I had a strong sense of the universality of the Church. The first bishops I met were from Lesotho, Darwin and Slovenia. I found myself sitting in the Synod Hall between a bishop from Fiji and another from Buenos Aires. I shared with the Fiji bishop that my mother’s cousin, a Columban missionary from Donegal, had worked for many years in Fiji. It turned out he knew of him! I was also able to share with my neighbour from Buenos Aires that my father’s cousin works there as a Christian Brother! There we were, three bishops from places thousands of miles apart, yet linked by a network of family, parishes and dioceses and by the missionary endeavour of the Irish Church.

It’s difficult for me to understand the Church without thinking of belonging, family and connections. Pope Francis has described the church as a ‘family of families’. The family in Catholic tradition is the ‘little church’, or domestic Church. Parish is a ‘’family of families’ linked by faith, place, priest, land, tradition. Diocese is a family of parishes, and, in turn, the universal Church links dioceses through faith in ‘one Lord, one faith, one baptism and one God who is Father of all, with all, through all and within all (Eph 4:5)’.

Patrick Kavanagh famously drew out the links between the parochial and the universal: “All great civilisations are based on the parochial”, he wrote and, again: “To know fully even one field or one land is a lifetime’s experience. In the world of poetic experience it is depth that counts, not width. A gap in a hedge, a smooth rock surfacing a lane, a view of a woody meadow, the stream at a junction of four small fields – these are as much as a man can fully experience”.

Strong links between family and Church are deep down in the spiritual psyche of Ireland. Unlike the continental model, in which Church structure was based on the Roman Imperial administrative units of ‘dioceses’ normally centred on major cities, monasticism in Ireland had facilitated more fluid, familial types of federations. The Irish words ‘muintir’ (family or people) and ‘mainistir’ (monastery) are closely linked. Irish ecclesiastical territories were based around ‘tuatha’ or tribes; the role of abbot was often passed down within families – and a lay leader (airchinnech or erenagh) often acted as administrative head of ecclesiastical units. When it came to the much needed twelfth century reform at the Synods of Rathbreasail (1111) and Kells (1152) the Church in Ireland was to some extent attempting to fit a continental system onto the pattern of ancient Irish ‘paruchiae’ that had emerged in the previous seven centuries.

My family had strong connections, growing up, with my local parish of St Patrick’s Pennyburn in Derry where I was an altar server, and later a reader and assistant sacristan. The priests of the parish were household names; home, school and parish closely cooperated in handing on the faith. Nowadays that sense of belonging is perhaps less significant in the life of the average Catholic, although this varies from area to area, from rural to urban. As bishop I’ve visited parishes where I’ve experienced a strong sense of identity and community, connection and belonging. However few would disagree that all forms of community have taken a battering in a culture where individualism, personal autonomy and choice are often paramount. Although social media links us in a great global network, still it can be shallow and cosmetic, fleeting or superficial.

Last summer I spoke to the parents of a practising Catholic family with two teenagers and two younger children. On a typical weekend the teenagers go to the early Vigil Mass in their neighbouring parish. Dad brings the youngest boy to football training early on Sunday morning and later they both go to Mass in the chapel of a Religious Congregation. Meanwhile, mum and five year old daughter go the children’s Mass in their own parish. The family seldom gets the opportunity to attend Mass together except perhaps at Christmas and Easter Sunday.

It is time for us to “sing a new song to the Lord” – to re-imagine parish and diocese in Ireland. In ‘The Joy of the Gospel’ (28) Pope Francis encourages a parish to be “a community of communities, a sanctuary where the thirsty come to drink in the midst of their journey, and a centre of constant missionary outreach”. The parish, he says “continues to be ‘the Church living in the midst of the homes of her sons and daughters’. This presumes that it really is in contact with the homes and the lives of its people, and does not become a useless structure out of touch with people or a self-absorbed cluster made up of a chosen few”.

We might ask to what extent are our parishes living, worshipping ‘communities of the faithful’ (Canon 515) with a sense of belonging and connectedness? To what extent is a parish a ‘community of communities’, a family of families? We are in a transition time between the relative security and certainties of past times and what discovering what the Spirit wants of the Church in Ireland today and tomorrow. It will impossible for us to hold on to the ways we lived parish in the past. The parishes of tomorrow will be ‘communities of intentional disciples’ sustained by committed and formed lay people. The key to this will be the formation of cells, or smaller gatherings of committed people who meet and pray and develop together their understanding of faith, and who find there the courage to engage in mission and outreach. Many parishes already have prayer groups, lectio divina groups, adult faith groups, youth groups or adoration teams. Each of these gives to its members a sense of belonging, identity, mission and vocation. Think also of Baptismal teams, bereavement or Bethany Groups – each of these is helping to build links and connections in which a person’s faith can grow, be expressed and strengthened.

What if we were to take this a step further? What if a number of families were to begin meeting together to pray, share their joys and struggles in faith, read the Word of God together, talk about their personal faith journey, discuss and study together aspects of faith, commit to mission, and then, on Sunday join together with similar cells or ‘families of familie’ in the Parish Sunday Eucharist? Something like this model is already being developed within the Neocatechumenal Way and in many of the new ecclesial movements that are springing up around Ireland. It will of course mean a certain amount of ‘letting go’ by priests and even bishops as the centre of gravity of life, worship and mission in the parish shifts from the parochial house or diocesan curia to the little domestic churches and gatherings of families on the ground. However the dividend for such a divestment could be more energised, connected families approaching Sunday Eucharist as the summit of their week and as the source of nourishment and life for the week ahead.

All of this might seem a strange thought process for me to engage in here at the home place of the great Seamus Heaney. But the more I read his poetry the more I sense his deep understanding of how people are connected to one another by their locality and their shared sense of place, history and tradition. Heaney develops somewhat his understanding of this ‘connectedness’ in his final volume of poetry, ‘Human Chain’ (2010) He certainly saw his home place as a liminal space or ‘aperture’ connecting him as a person to the world at large, to times past in Ancient Ireland, Rome or Greece, and even to the infinite and transcendent.

As believers we are challenged to find ways of opening the lives of people today to the transcendent, to the God who gives life its foundation and purpose. In one of my favourite Heaney poems, ‘St Kevin and the Blackbird’, the kneeling saint, with arms outstretched in prayer, shelters in his upturned palm the nest of a blackbird until its young are ‘hatched and fledged and flown’. In an act of complete generosity, the saint links his whole being with the transcendent, eternal God, forgetting himself entirely.

Alone and mirrored clear in love’s deep river,

‘To labour and not to seek reward,’ he prays,

A prayer his body makes entirely

For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river’s name.

There is an absence in the lives of so many people today of any sense of the eternal; there are few opportunities in this hectic world to connect with the infinite. Our task, as people of faith, is to share with others ‘the reason for the hope we have within us’ – the joy of a personal, loving relationship with God.

Seamus Heaney was not easily drawn on the subject of his own spirituality – perhaps it was a case of, as he quipped in ‘North’ (III), ‘whatever you say, say nothing’; ‘religion’s never mentioned here’. He was certainly steeped in the tradition, culture and mystery of the faith in which he was raised and, despite expressing occasionally his doubts and lapse, he never once to the best of my knowledge, profaned or disparaged the religion of his youth. In ‘A Found Poem’ (2005), he shares so honestly:

There was never a scene

when I had it out with myself or with an other.

The loss of faith occurred off stage. Yet I cannot

disrespect words like ‘thanksgiving’ or ‘host’

or even ‘communion wafer.’ They have an undying

pallor and draw, like well water far down.

His son shared with us that, in the minutes before he died, Seamus Heaney sent a text message to his wife Marie saying Noli Timere – do not be afraid. Despite all the words he himself had written, he could think of no greater gift than the consoling Word, central to the Judeo-Christian tradition of an all-loving, all-merciful God. Heaney has hinted that

his love of words was nourished by the mystique and beauty of the liturgy like the litany of the Blessed Virgin his family used to recite at home, connected together in prayer – “Tower of Gold, Ark of the Covenant, Gate of Heaven, Morning Star, Health of the Sick, Refuge of Sinners, Comforter of the Afflicted.”

On the day of his burial I had the privilege of walking with his loved ones in the funeral procession to his final resting place in a corner of St Mary’s Churchyard, Bellaghy. Just as the prayers ended I had the privilege of leading with the other priests present the singing of the Salve Regina. Marie and many around us joined in. For a moment we were all linked ‘in between’ – family, friends, neighbours, priests, believers and non- believers alike, ‘sending up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears’, but looking to heaven forgetting self, forgetting earthly barriers, forgetting Bellaghy even.

You must be logged in to post a comment.